Selling on Amazon can bring a plethora of benefits, from seamless scalability to that coveted stream of extra income. But as any business owner would know, great profits come with great financial responsibilities—budgeting, cash flow management, cost control, and of course, taxes.

The latter can be daunting, even for the most seasoned online seller. You might have questions like, “Do I have to report Amazon sales on my taxes?” or “How do you file taxes for Amazon’s FBA program?”

Worry not. We’re here to break down everything you need to know so you can get your Amazon seller taxes sorted before Tax Day (April 15).

Understanding the Basics of Amazon Seller Taxes

Several factors play a role in determining your tax liability as an Amazon seller. Some notable ones include your location, the buyer’s location, and the kind of products you are selling. Knowing this information upfront is the first step to navigating the world of e-commerce taxation like a pro.

That being said, let’s walk through the types of taxes applicable to sellers on Amazon.

- Sales tax: A tax on goods and services collected by sellers from customers at the point of purchase.

- Income tax: A tax on an individual’s or business’ income. Make sure to report and pay this tax on any profits earned through Amazon—it’s all part of keeping those finances in check.

- International tax: If selling outside of the country, you may incur additional taxes such as the value-added tax (VAT). We’ll delve more into this topic later on.

A Deep Dive into Sales Tax for Amazon Sellers

Now that we’ve discussed the basics, it’s time to take a closer look at how sales tax works on Amazon. The e-commerce giant is classified as a Marketplace Facilitator, or a marketplace that contracts with other businesses and promotes their goods. As a result, they must calculate, collect, and remit any sales tax on behalf of the seller in states where it is mandated.

Not all states have enacted Marketplace Facilitator legislation so it is up to you to stay on top of your tax obligations.

Follow the steps below to ensure your sales tax compliance. Even if Amazon collects sales tax for you in certain states, there might be instances where you’ll have to do it yourself.

How to Collect Sales Tax on Amazon

- Figure out your sales tax nexus

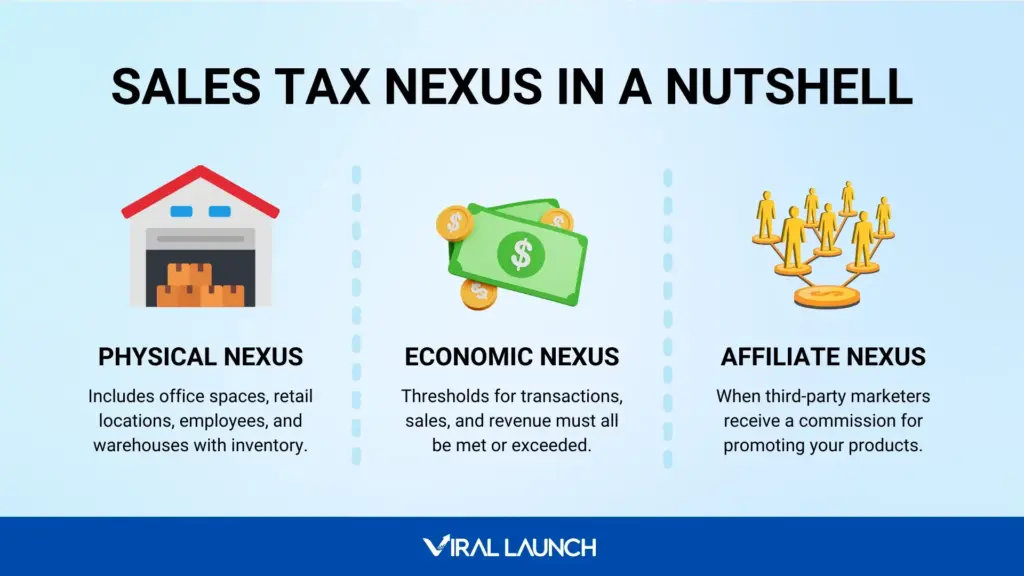

Generally speaking, sales tax nexus determines if your business has enough presence in a state for you to be required to collect sales tax. The location of your business and reaching a state’s sales threshold are just a few constituents that can help identify this.

If you work in Massachusetts but have staff in New Jersey, you would be responsible for the sales tax in both of those states.

- Register for a sales tax permit

It is imperative that you don’t skip over this step. Without a permit, you will not be able to legally collect and remit sales taxes. You might have to register with one state or multiple states, but it will all depend on where you have nexus.

Once you have acquired any necessary permits, the government will send you information on when to file. See that you stick to those deadlines or you may have your permit(s) revoked.

- Set up sales tax collection in Seller Central

Go to “Tax Settings” in the drop-down menu and click on “View/Edit your Tax Collection and Tax Obligations.” There, you can select the states you’ll be collecting taxes in, as well as enter your state tax registration number and relevant product tax codes (PTC’s). Doing so will help Amazon know what sales tax rates to charge on eligible products.

FBA Tax Obligations

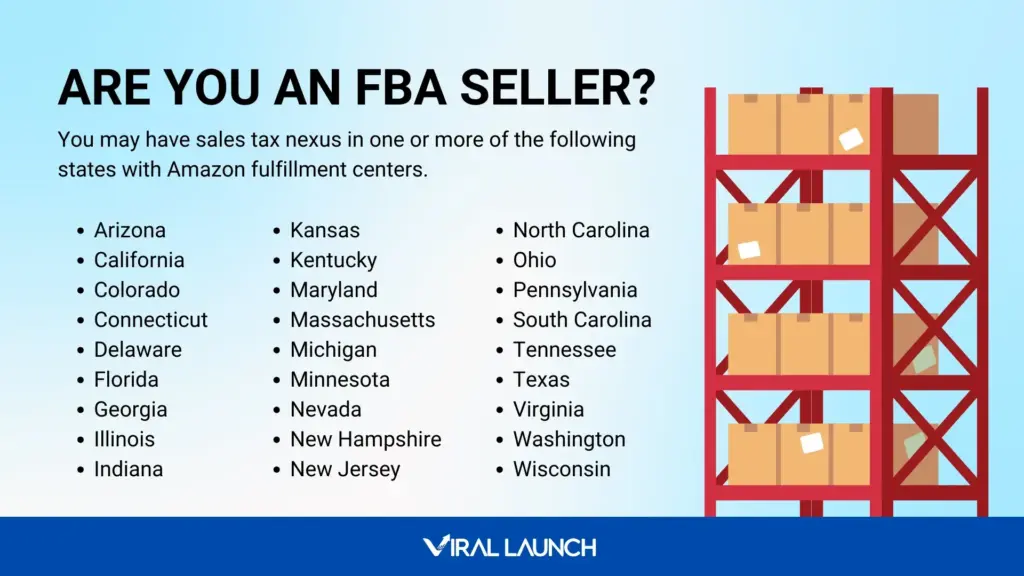

If you’re an online retailer who uses Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA), the last thing you’d want is an unforeseen sales tax nexus in a state. Given that Amazon stores inventory in its fulfillment centers across the U.S., the chances of establishing nexus beyond your home state is highly likely.

How can you expect the unexpected, then?

Do your research. Read up on the rules and regulations of Amazon FBA taxes. Learn what items are taxable and which states charge sales tax. You’ll thank yourself come tax season.

Federal Income Tax Considerations

Your guide to Amazon seller taxes wouldn’t be complete if we didn’t discuss the good old income tax. It has its differences from the sales tax, which are highlighted below.

| Income Tax | Sales Tax | |

| Based on | Profits | Revenue |

| Paid to | The federal government through the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and potentially a state government | State and local governments |

Now, you may be questioning what qualifies as taxable income. As a general rule of thumb, your gross annual income on Amazon counts toward it. That includes anything from the amount your customers paid for products to shipping charges. The good news, however, is that you can implement tax deductions and strategies to maximize your tax savings.

Deductions and Credits for Amazon Sellers

Think of a deductible as a business expense. If an item is essential to your operations, then it can be written off. Remember to keep any business-related receipts on hand; it could help lower the amount of taxes you owe.

Here’s a list of common deductions to help you determine what qualifies as a write-off.

- Amazon fees contributing to the costs that come with running your business

- Business travel

- Consulting services

- Cost of goods sold (COGS) including labor, production costs, and wholesale prices

- Education related to e-commerce and running an online business

- Home office expenses

- Online advertising

- Software for payroll, website hosting, email services, or even Viral Launch’s Amazon optimization tools.

And here are the thresholds for standard deductions, which have gone up since 2024.

- Single Filers: Increased to $15,000

- Married Filing Jointly: Increased to $30,000

VAT (Value-added Tax) for Amazon Sales

One more piece to consider is the taxes that go beyond the United States. Yep. If you’re selling overseas, certain taxes will apply to you.

Take the VAT (Value Added Tax), for instance. Products and services are taxed based on the value added to them as they go through the supply chain. Because it is a consumption tax, consumers are responsible for paying VAT. Sellers, however, will need to collect and remit the tax to the government.

You’ll find that many countries such as those in the European Union (EU) employ VAT. Regardless where you do business in, there will be tax jurisdictions you need to follow. We’ve outlined some essential information below to help you get started on becoming VAT-compliant.

- Register for a VAT Identification Number (VATIN)

A VATIN is assigned to your business for value-added tax purposes. If you’re planning to import, store, or sell goods in the EU, for instance, one or multiple numbers may be required depending on which countries you’re selling in.

If you’re unsure whether you need to register for one at all, consult a tax professional. You can also learn more about selling on Amazon Europe in our guide to EU VAT.

- Know your VAT rates

VAT rates will vary depending on the country and the type of product being sold. For the EU, the standard rate must be at least 15% but you can check out each country’s rate here.

The Essentials for Tax Reporting & Filing

Knowing your tax obligations is just half of the equation; the other half is understanding what you need for tax reporting and filing. A great place to start is familiarizing yourself with the appropriate Amazon tax documents.

Form 1099-K

| What is Form 1099-K? | A tax form used to report monthly and annual gross sales earned from Amazon and other third-party businesses. |

| Does Amazon issue Form 1099-K to sellers? | Yes, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) requires Amazon to send this form to sellers who have: – Made over 200 transactions in a year – Achieved over $5,000 in gross sales for the 2024 tax year – Achieved over $2,500 in gross sales for the 2025 tax year *Note that the thresholds for gross sales have been reduced from $20,000. |

| Where can I find Form 1099-K? | If you’ve fulfilled the above requirements, Amazon has probably sent you your Form 1099-K for the year. But you can also access it by going to the “Reports” menu and selecting “Tax Document Library” in Seller Central. |

| What if there are errors on my Form 1099-K? | There are cases when an Amazon seller’s tax information is inaccurate on Form 1099-K. Not to worry, though. You can check for potential mistakes with these steps: 1. Confirm that you’re documenting the unadjusted total gross sales for the year. Remember to go off shipping dates, and not sales dates. A sale made on December 31, 2024 will not appear on the report if it shipped out on January 1, 2025. 2. Print a date range report in Seller Central to verify the information on your 1099-K form. Go to the “Reports” tab > “Date Range Reports” > “Generate a Statement.” You’ll get a “Generate Date Range Report” popup. Choose “Summary” as the report type and “Monthly” or “Custom” with the appropriate date information as the reporting range. Hit “Generate” and wait for your report to be created. This can take up to an hour. Review the report and calculate your unadjusted gross sales by adding together the figures from the report columns in the two charts. |

Schedule C (Form 1040)

Do you own and run your business? Have a business license in your state? If so, you’ll need to add the Schedule C (Form 1040) to the list of Amazon seller tax forms needed. It’s used to report your profits and losses.

You may be wondering if you need a business license to become an Amazon seller. The short answer is no, but some states may require you to get one. Be aware that the criteria for obtaining a license can differ by state. However, having employees, offices, or inventory in multiple states most likely means you will need one.

How to File Taxes as an Amazon Seller

After gathering the necessary information and tax forms, you can file your taxes in one of three ways:

1. Through a tax professional

We highly recommend you work with a tax expert if your budget allows for it. They can help you manage your Amazon income tax reporting, understand state sales tax laws, maximize tax deductions, and much more.

2. Using tax software

You’ll be guided through the tax filing process, but you should still be diligent about reviewing your work to avoid making costly filing errors.

3. By doing it yourself (DIY)

If you prefer, file via state tax websites and directly with the IRS. Consider this option only if you 100% understand your tax obligations. Similar to our advice for those using a tax filing program, check over everything.

Simplify Tax Day with Viral Launch

As Tax Day approaches, make sure you’re equipped with the resources that help you stay informed and compliant, and minimize your tax expenses. Using tools like Viral Launch can provide detailed insights into net profit margins, total revenue, units sold, ROI, PPC costs, and more—all of which you can leverage to help manage your finances.

To make this time of year less of a headache, consider hiring a tax expert to assist you with your accounting needs. Viral Launch has partnered with 1-800Accountant, America’s leading virtual account firm, to provide you with a free tax saving analysis. Sign up today to speak with a trusted Amazon accounting professional for expert advice on optimizing your business finances while maximizing your profits.

On that note, we wish you the best of luck this tax season.

Additional Resources

Tune into Episode 13 of The Seller’s Edge Podcast where 1-800Accountant’s Gary Milkwick shares small business tax hacks for financial success.